Records management is an unglamorous but essential part of the operation of any organization. The computerization of the workplace brought about some paradoxical changes (see Computers and the Death of Recordkeeping) and the rise to prominence of Artificial Intelligence has resulted in renewed interest in automatic classification replacing the historical role of the filing clerk.

Google and Organizational Search

The spectacular success of Web search engines such as Google in retrieving desired information naturally makes people wish they could replicate its success within organizations that they work for. Google realized this too and the history of the Google Search Appliance (which reaches its official end of life in 2019, after 17 years) illustrates their ultimately unsuccessful attempt to provide this. The basic reason for this is that there are seldom any hyperlinks to use for ranking search results within organizations. Ranking tends to be by keyword frequency , which gives poor results. No other search vendor has done any better, but a number of specialist Records Management companies are tackling this problem with automatic classification – assigning documents to file plan categories using automated methods. As paper records management gives way to digital, the problems of effective management of organizational records become more obvious and vendors are jumping into the opportunity.

BORN Digital

One problem at least is becoming less serious – as born-digital documents extend further into the past, the task of extracting machine-readable text from scanned document images is diminishing, and technical improvements in optical character recognition mean that extracted text from scanned documents is more likely to represent what was written than in the past. However, the task of grouping and classifying documents in the manner in which filing clerks used to operate has not seen a similar improvement.

Automatic Classification

There are

two main methods of automatic classification: rule-based and training set

based. Rule-based classification has a long history (back to the 1970s) and is

simple to apply and understand. The occurrence of a word or phrase in a

document, or words or phrases in proximity to each other is sufficient to

indicate membership of a particular class. In the simplest case, a single

occurrence of word or phrase is sufficient to place a document into a

particular class. This approach is used by products intended for tagging rather

than records management. Variants of this approach use statistical rather than

binary classification, and may perform deterministic processing of text (such

as word stemming) to improve performance. The task of defining a set of rules may

be purely manual or may use a training set of already classified to identify

words and phrases occurring more commonly in a particular class to generate

rules semi-automatically.

Why AI can’t help much within organisations

Modern Artificial Intelligence classification may use neural nets to perform classification, treating words and phrases simply as tokens in the same way as features extracted from images. Such methods require large training sets and the rules generated are unknowable, and cannot be easily edited. The token –based analysis means that if words in text content are randomly re-ordered, turning the document into gibberish, the classification result remains unchanged, except for effects caused by the disruption of phrases. As more documents are classified, and the classifications approved, the number and quality of rules may increase, allowing vendors to claim that that their systems learn from experience. However, the lack of transparency of the rules used by networks means that the content of documents unrelated to its meaning (such as an organization’s address) may end up forming the basis of a classification rule.

Non-explicit content

Another

problem with content-based classification is that the most important

classification features of documents created for a small audience are not

explicitly mentioned, as anyone viewing the document was assumed by its creator

to know what it was about. A specific example from one company was a document

relating to problems encountered with an Oracle database upgrade. The content

never mentioned the word “Oracle” and

only referred once to the version number of the database. The document name and

provenance often are a much better guide to classification than the text content.

If google translate is so good, why can’t it classify my documents?

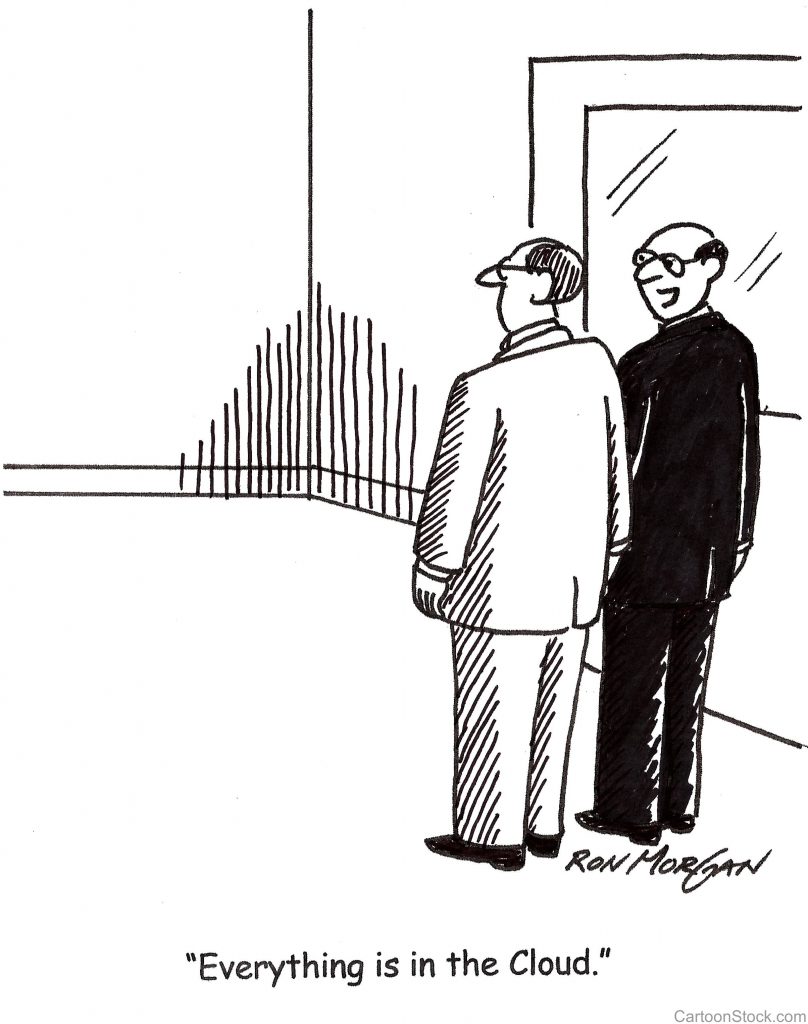

The

increasing power of computers, and particularly the availability of massive

cloud resources, masks the fact that automatic classification (and machine

translation between languages) is based on statistical analysis of words and

phrases, not on their meaning, as extracted by any human reader. The nuances of

language are such that even the detection of negation in a text is a PhD topic,

like deciding whether the sentence “Time flies like an arrow” is a statement

about a type of fly or about human experience. The spectacular success of

Artificial Intelligence in playing

rule-based board games such as chess and Go does not involve any automated understanding

of the complexities of language use, and its success in quiz games is based

more on good database design than anything else. Reputedly, when IBM’s Watson

was asked “Who was the first woman in space?” its answer was “Wonder Woman”, as

it had no concept of the distinction between fiction and non-fiction.

Notwithstanding

the limitations of statistical classification, any type of classification is

usually better than none, even with a high error rate, but expectations should

be tempered. The problem of language understanding may well be cracked in the

future and automated filing clerks will become available, but we are certainly

not at this stage yet.