Once upon a time, organizations needed a physical presence that people could visit in order to engage with it. With the rise of virtual interactions, the need for a physical presence has diminished, and web sites, which are far cheaper than offices, have become the means of engagement with clients. This change has benefited small organizations greatly but has made the task of collaboration between organization staff more difficult. It’s not possible to walk over to someone’s office or cubicle to discuss something, or to look through a ring-binder for an important document. Tagging documents and emails can help but with virtual infrastructure it can be complicated.

Is the cloud the answer?

Cloud-based electronic management and collaboration software has filled this gap to a certain extent, with hundreds of products available, all offering to boost organizational productivity and requiring only a web browser and Internet access to use them. Users can just as easily be on different continents as in the same office. However, with products attempting to lock in users, migration between competing systems is often difficult, and the nirvana of search technology accurately retrieving desired electronic documents is seldom achieved.

One reason for this is that keyword search for a word or a phrase does not always come up with only the documents that the user is searching for, and the ranking of the desired document may be much lower than documents that are not being sought. Search engines such as Google have the massive advantage of knowing what you (and others) have searched for and looked at already, and this knowledge helps them deliver the documents you’re looking for close to the top of the search results. The performance of search in electronic document management and collaboration systems is almost always disappointing compared to Web search.

Assumed Knowledge and lack of text

Another problem is that the text content of an authored document may not give any indication of what is about, as the intended audience could be assumed to know this already. A classic example of this was a document about problems with a new version of a database system found in a consumer goods company. The name of the database system did not appear in the text, as the author of the document assumed that everyone reading it would know which database system the company used.

The document may not contain any text: digital photos are increasingly used for a variety of purposes within organisations. Image analysis (as performed by Google Photos, Windows Photos, and many other products) attempts to automatically add information on the subject of the photo, and mobile phone photos will automatically add time and location data, but the level of detail provided by automatic means is seldom sufficient.

What’s The Answer

In the pre-computer workplace, responsibility for information storage and retrieval lay with specialist registry staff who managed collections of paper files for the organisation. Their decisions on what file a particular document, or folio, belonged on were slow and sometimes idiosyncratic but consistent across the organisation. The jobs of these staff were usually the first to go as organizations became computerized, with the movement of paper files on the “filing ferry” being replaced by access to electronic documents on a shared filesystem. What was not replaced was their knowledge of the hierarchy of information storage within the organisation.

Tagging documents

The application of user-generated metadata (most usefully, content-related tags) to documents is built into many electronic document management and collaboration systems, such as Microsoft SharePoint. This facility allows users to add a controlled set of metadata to any document being checked into the system, and this tagging process can be made mandatory. This process devolves the classification task once performed by specialist registry staff, to any person with access to the repository.

In principle, this is a good idea. However, people creating and checking in documents may not have the time or training to choose the correct content-related tags, especially if they have to choose from dozens of options. They may also use other locations than the repository to store their documents if these are available. Some systems claim to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to correctly classify any document on ingestion, but performance in a demonstration is seldom matched by performance in a working environment.

Multiple repositories

If the user environment comprises mainly documents stored on the Web then a method of adding controlled metadata to these documents, and retrieving them on the basis of metadata values is required. Many systems provide these features: the problem is that multiple systems may be used. For example, an organisation may use SharePoint within Office 365, but also have other documents in DropBox or Google Drive and use a web-based mail client.

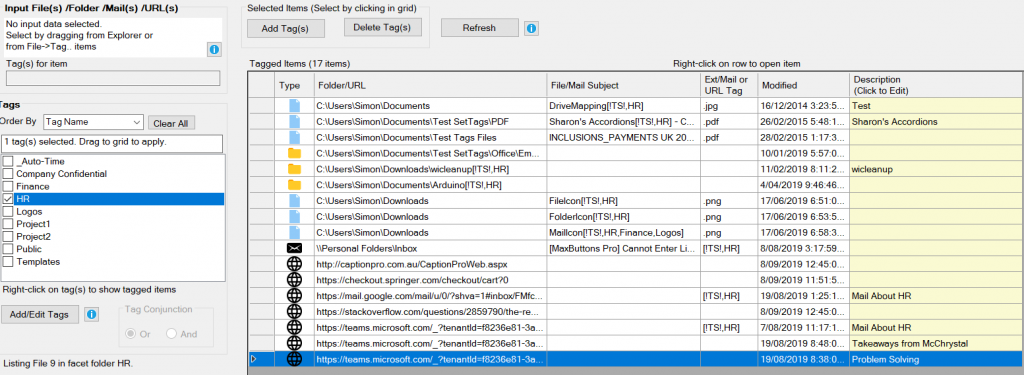

SetTags allows users working in a minimal infrastructure environment to perform tagging from a controlled set of tags to local files and folders, URLs and Outlook mail messages, and to list all these items on the basis of their tags from a convenient Windows desktop application. A description can be added where the attributes of the item do not indicate its content. The items can be opened by double-clicking.